His Holiness Paul VI (21 June 1963-6 Aug. 1978) was the son of a prosperous lawyer who was also a political writer and parliamentary deputy, and of a pious mother to whom he was devoted. Giovanni Battista Montini was born at Concesio, near Brescia, on 26 September 1897. Shy and of precarious health, but with an appetite for books, he attended the diocesan seminary from home, was ordained on 29 May 1920, and then pursued graduate studies in Rome. From 1922 he worked in the papal Secretariat of State, a brief spell (May-Nov. 1923) in the Warsaw nunciature being broken off for health reasons. Continuing in the Secretariat, he became deeply involved (1924-33) in the Catholic student movement, and from 1931 also taught diplomatic history at the papal academy for diplomats. On 8 July 1931 he was made a domestic prelate to the Holy See, and on 13 December 1937 assistant to Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, then Secretary of State. When Pacelli became Pius XII in 1939, Montini continued to work closely with him, being assigned responsibility for internal Church affairs in 1944. Promoted Pro-Secretary of State in November 1952, on 1 November 1954 he was appointed Archbishop of Milan, a vast diocese beset with social problems. Aspiring to be ‘the workers’ archbishop’ and accompanied by his now legendary ninety crates of books, he threw himself with immense energy into the task of restoring his war-battered diocese and establishing strong ties with the industrial workers and their families; for three weeks in November 1957 he carried out an intensive mission aimed at reaching every parish in the city. During such activities as a missioner and diocesan, he also found time for experiments in Christian unity, holding discussions, for instance, with a group of Anglicans in 1956. On 5 December 1958 John XXIII named him a Cardinal, and as that Pope’s close adviser he played a noteworthy part in the preparations for Vatican Council II (1962-5). During these decades he travelled widely, visiting Hungary (1938), the USA (1951 and 1960), Dublin (1961), and Africa (1962). At the conclave of June 1963, attended by eighty Cardinals and the largest so far in history, he was elected as John XXIII’s successor at the fifth ballot. He chose a name which suggested an outward-looking approach. Following in the footsteps of his predecessor, Paul VI immediately (22 June) promised to continue Vatican Council II, interrupted by John XXIII’s death; he also later revised canon law, promoted justice in civil, social, and international life, and worked for peace and the unity of Christendom (a theme that would become increasingly close to his heart).

Paul VI opened the second session of the Council on 29 September 1963, introducing important procedural reforms (e.g. the admission of laymen as auditors, the appointment of four moderators, and the relaxation of confidentiality), and closed it on 4 December 1963, promulgating the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy and the Decree on the Mass Media. On 4-6 January 1964 he made an unprecedented pilgrimage by air to the Holy Land, meeting Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I in Jerusalem. Having on 6 September announced the admission of women, religious and lay, as auditors to the Council, he opened the third session on 14 September 1964 and closed it on 21 November 1964, promulgating the Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium (with a note attached explaining the collegiality of bishops, i.e. the doctrine that the bishops form a college which, acting in concert with and not independently of its head, the Pope, has supreme authority in the Church); the Decree on Ecumenism Unitatis Redintegratio (modifying several passages on his own authority); and the Decree on the Eastern Catholic Churches Orientalium Ecclesiarum; he also proclaimed the Blessed Virgin Mary ‘Mother of the Church’. During the recess he flew (2-5 Dec. 1964) to Bombay for the International Eucharistic Congress. At the fourth and last session of the Council (14 Sept.-8 Dec. 1965), during which he flew to New York (4 Oct.) to plead for peace at the United Nations, he undertook to establish a permanent Synod of Bishops, with deliberative as well as consultative powers. Before mass on 17 December 1965 a joint declaration by himself and Patriarch Athenagoras I was read out deploring the mutual anathemas pronounced by representatives of the western and eastern Churches at Constantinople in 1054 and the schism which resulted. The following year, he solemnly confirmed all the decrees of the Council, and proclaimed an extraordinary Jubilee (1 Jan.-29 May 1966) for reflection and renewal in the light of the Council’s teachings.

Paul VI then began implementing the Council’s decisions with courage and an awareness of the difficulties involved. He set up several important post-conciliar commissions (e.g., for the revision of the breviary, the lectionary, the order of mass, sacred music, and canon law), and carried through the substitution of the vernacular in the liturgy with determination. He reorganised the Curia and the Vatican finances and confirmed the permanent Secretariats for the Promotion of Christian Unity, for Non-Christian Religions, and for Non-Believers. In pursuit of ecumenism, he held meetings with the Archbishop of Canterbury (Dr. Michael Ramsey) in Rome (24 Mar. 1966), and with Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I in Istanbul (25 July 1967) and Rome (26 Oct. 1967). In May 1967 he flew to the shrine of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Fatima, Portugal, to pray for peace. His public pronouncements included Mysterium Fidei (3 Sept. 1965), paving the way for liturgical reform and reasserting traditional Eucharistic doctrine; Populorum Progressio (26 Mar. 1967), a plea for social justice; Sacerdotalis Caelibatus (24 June 1967), insisting on the necessity for priestly celibacy; Humanae Vitae (25 July 1968), condemning artificial methods of birth control; and Matrimonia Mixta (31 Mar. 1970).

From 1967 to 1970 Paul VI carried out nine international journeys to the five continents of the world, both to stress the universality of the Church and to lend weight to his more general policy of internationalisation. The journeys of this ‘pilgrim Pope’ included those to Geneva to address the International Labour Organisation and the World Council of Churches, and to Uganda to honour its martyrs, in June and July 1969 respectively; to Sardinia to celebrate Our Lady of Bonaria in April 1970; and to the Far East (where he narrowly escaped assassination in Manila) in November-December 1970. On 25 October 1970 he canonised forty English and Welsh Roman Catholic martyrs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; he also proclaimed St. Teresa of Avila (1515-82) and St. Catherine of Siena (1347-80) Doctors of the Church, the first women to be so denominated. In the same year he fixed the retirement age for priests and bishops (75), and decreed that Cardinals over 80 should not participate in Curial business. In furtherance of collegiality, he convened international episcopal synods in 1971 (on the priesthood), in 1974 (on evangelisation), and in 1977 (on catechesis). In April 1977 he and the Archbishop of Canterbury (Dr. Donald Coggan) issued a ‘Common Declaration’ which pledged united work towards reunion. One of his most important legacies to the Church, brought to completion in this closing phase, was his steady enlargement and internationalisation of the Sacred College. When he was elected it had some 80 members, but by 1976 he had raised the total to 138; moreover, by that latter date its Italian members were a small minority, and it contained many representatives from the third world.

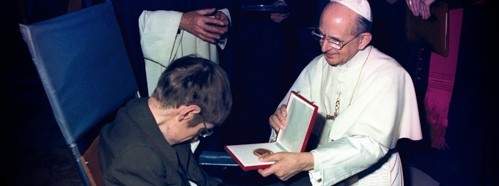

Characteristically, Paul VI sought to make the papacy less formal and sold the tiara presented to him at his election for the benefit of the poor. In his last year he was profoundly disturbed by the kidnap and eventual murder (May 1978) of his lifelong friend Aldo Moro, the Christian Democrat statesman. Paul VI’s last public appearance was to preside at his funeral in St. John Lateran, at which he declared: ‘You have not answered our implorations for the safety of Aldo Moro, but You, O Lord, have not abandoned his immortal spirit’. A few months later Paul VI was stricken with arthritis, and after suffering a heart attack he died at Castel Gandolfo on 6 August 1978, bequeathing a famous spiritual testament which bore witness to his innermost feelings and sentiments. On 11 May 1993, in the diocese of Rome, the procedure was set in motion for his canonisation.

Paul VI appointed 56 new members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, amongst whom were such prominent figures as: D. Baltimore, A. Bohr, G. Colombo, C. de Duve, G. Herzberg, H.G. Khorana, J. Lejeune, L.F. Leloir, R. Levi-Montalcini, G.B. Marini-Bettòlo, R.L. Mössbauer, M.W. Nirenberg, S. Ochoa, D.J.K. O’Connell, G.E. Palade, G. Porter, M. Ryle, B. Segre, R.W. Sperry, R. Stoneley and A. Szent-Györgyi. His pontificate also witnessed, for the first time, a member of the laity as President of the Academy: the Brazilian C. Chagas. In his official papal pronouncements in both written and oral form, Paul VI frequently stressed the importance of the two separate branches of knowledge of faith and reason, which he argued could work in harmonious tandem, and he also drew attention the legitimacy of the pursuit of truth through reason. He also pointed to the obstacles created by the development of specialisation and warned against the dangers of not achieving an overall vision of reality.

Paul VI gave nine papal addresses to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and on these and other occasions he strongly emphasised that the progress of science should have a strong moral and ethical dimension and work to the benefit of man in all his aspects. This formed a part of his general view, following on from Pius XI, that knowledge had an inherent and necessary ‘charity’. Here we will recall those topics which in a special way served as guides and stimuli for the activities of the Academy. In 1966, at the reception of the Academicians and other scientists taking part in the study week on molecular forces, Paul VI reconfirmed the links that exist between man and science, and recalled that the Church recognises and values the importance of scientific research, just as she admires and encourages the intellectual and organisational efforts which are necessary to undertake such research. In Paul VI’s opinion, a scientist, because of his moral qualities and his devotion to his work is ‘an ascetic, and sometimes a hero’ to whom the whole of humanity is indebted. But science alone is not sufficient because it is not an end in itself: ‘science can only exists thanks to man, and it is by man’s intervention that it must break out of the mere world of research in order to reach out to man and therefore to society and to history itself’. But after this acknowledgement he went on to address a question to scientists regarding the ethical norms which regulate the way science should be applied. He touched upon the ethical problems connected with the use of science in fields such as genetics, biology, atomic energy, emphasising the fact that a scientist cannot and must not avoid asking himself what the effects of his discoveries on the psycho-physiological nature of the human personality might be. Paul VI expressed to scientists the beautiful concept of ‘knowledge as charity’, reminding those who hold the key to advanced culture that there are a countless number of people who are rarely aware of more than scattered fragments of the vast field of human knowledge. In 1972, at the audience granted to the Academicians and scientists who had attended the study week on fertilisers, Paul VI gave another important speech. Amongst other things, he referred to the point of contact between scientists and nature, underlining the risk of falling into a state of bewilderment in those cases where scientific results are not considered from a transcendent point of view. ‘Human intelligence is a spark which belongs to the absolute light which has no shadows’. He went on to affirm: ‘whatever progress we make, whatever synthesis we achieve reveal a little more to us of the plan which governs the universal order of existence and the efforts of humanity as a whole to make progress. We are searching for a new humanism which is capable of allowing modern man to find himself again, by voluntarily accepting the higher values of love, friendship, prayer and contemplation’. Nor did Paul VI limit himself to quoting the above sentence of Populorum Progressio. Taking his inspiration from the efforts of scientists to increase soil fertility, he stressed the importance of the problems of world hunger and the absolute necessity for social justice.

In his address of 23 October 1976, when welcoming those taking part in the study week on natural products and plant protection, he repeated his conviction that science should be placed at the service of man: ‘Sciences tend to overcome those barriers which men themselves have set up … science encourages the development of a mentality which seeks open, sincere and respectful dialogue with whoever is involved in working for man’s common destiny’, and emphasised that the research and activity of the Academy were an important instrument in promoting reciprocal understanding. Thus he declared: ‘It can be clearly seen, then, what an instrument of mutual understanding and peace serious scientific research can represent, and what a contribution the Assembly which you constitute can make from this point of view to promoting a more united and peaceful life among the nations’. Quoting the words of the great Pontiff, Pius XI, Paul VI expressed the wish that the Academy would become an increasingly rich source of beneficial charity which Truth is. Reference should also be made to his observation, made during his address of 15 April 1975, that the Academy could and should render a signal service to mankind by promoting a greater knowledge of nature and an improvement in conditions of life.