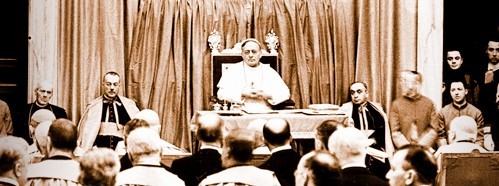

His Holiness Pius XI (6 Feb. 1922-10 Feb. 1939) was born on 31 May 1857 at Desio, near Milan, the son of a silk-factory manager, Ambrogio Damiano. Achille Ratti was ordained on 27 December 1879 in the Lateran; obtained three doctorates at the Gregorian University, Rome; was professor 1882-8 at the seminary at Padua; and worked 1888-1911 at the Ambrosian Library, Milan. An expert paleographer, he edited the Ambrosian missal and published other works; in his spare time he was noted for being a keen mountaineer. Moving to the Vatican Library in 1911, he became its Prefect in 1914. In April 1918 Benedict XV, recognising his flair for languages, sent him as Apostolic Visitor to Poland, promoting him Nuncio and Archbishop of Lepanto in October 1919. He carried out his difficult mission with skill and credit, refusing to leave Warsaw in August 1920 when a Bolshevik attack threatened. Benedict XV then appointed him (13 June 1921) Archbishop of Milan and Cardinal, and the following year, at the conclave of 2-6 February, he was elected at the fourteenth ballot. Pius took as his motto ‘Christ’s peace in Christ’s kingdom’, interpreting it as meaning that the Church and Christianity should be active in, and not insulated from, society. Hence his inauguration in his first Encyclical (Ubi Arcano Dei Consilio; 23 Dec. 1922) of Catholic Action, i.e. the collaboration of members of the laity with the hierarchy in the Church’s mission; his introduction of Catholic Action to numerous countries; and his encouragement of specialised groups such as the Jocists, a Christian youth organisation for workers. Hence, too, his institution of the feast of Christ the King (Quas Primas; 11 Dec. 1925) as a counter to contemporary secularism, and his employment for this purpose of the Jubilee years 1925, 1929, and 1933, as well as biennial Eucharistic congresses. The same theme, with different emphases, reappears in such Encyclicals as Divini Illius Magistri (31 Dec. 1929), on Christian education; Casti Connubii (30 Dec. 1930), defining Christian marriage and condemning contraception; Quadragesimo Anno (15 May 1931), reaffirming but going beyond Leo XIII’s social teaching, and its supplement Nova Impendet (2 Oct. 1931), prompted by contemporary unemployment and the arms race; and Caritate Christi Compulsi (3 May 1932), a response to the contemporary world economic crisis. His numerous canonisations were also intended to promote the same religious ends. They included John Fisher (1469-1535), Thomas More (1478-1535), John Bosco (1815-88), and Theresa of Lisieux (1873-97); he also declared Albertus Magnus (c. 1200-80), Peter Canisius (1521-97), John of the Cross (1542-91), and Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) Doctors of the Church.

In dealing with political issues after the First World War, Pius was assisted by his able Secretaries of State, Pietro Gasparri (1922-30) and Eugenio Pacelli (1930-9; later Pius XII). To regularise the position and rights of the Church, he concluded concordats or similar agreements with some twenty States. In France he brought about a substantial improvement in Church-State relations, expressing in Maximam Gravissimamque (18 Jan. 1924) a practical accommodation on the difficult issues arising out of the Law of Separation of 1905. His most significant diplomatic achievement was the Lateran Treaty (11 Feb. 1929) which he negotiated with Benito Mussolini, Italian Prime Minister since 1922, which established the Vatican City as an independent and neutral State. For the first time since 1870, the Holy See recognised Italy as a kingdom with Rome as its capital, while Italy indemnified it for the loss of the Papal States and accepted Catholicism as the official religion of the State. As time went on Pius XI was increasingly worried about the threat of the new totalitarian States. His repeated efforts to check Soviet anti-Christian persecution had no effect and in Divini Redemptoris (19 Mar. 1937) he condemned atheistic communism as ‘intrinsically perverse’. He negotiated (20 July 1933) a concordat with National Socialist Germany, but in the period 1933-6, because of its increasing oppression of the Church, he addressed thirty-four notes of protest to the Nazi government. The break came in 1937 when he ordered the Encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge (14 Mar.), denouncing repeated violations of the concordat and branding Nazism as fundamentally anti-Christian, to be read from all pulpits. In the twenties and thirties he protested several times against the fierce persecution of the Church in Mexico, and in April 1937 urged Mexican Catholics, when the situation had eased, to organise peacefully and promote Catholic Action. On 3 June 1933 (Dilectissima Nobis) he denounced the harsh separation between Church and State carried through in Spain by the Republican government. His attitude towards Italian Fascism, shaken in 1931 when Mussolini dissolved Catholic youth movements, dramatically hardened in 1938, when the regime adopted Hitler’s racial doctrines.

Strongly committed to overseas missions, Pius XI required every religious order to engage in missionary work, with the result that the number of missionaries doubled during his pontificate. Following Benedict XV, he pressed on with developing an indigenous Catholicism, personally consecrating the first six Chinese bishops on 28 October 1926. This was followed by consecrations of a native Japanese bishop (1927) and native priests for India, south-east Asia, and China (1933). In addition, the total of native priests rose during his pontificate from under 3,000 to over 7,000. He also founded a faculty of mission studies at the Gregorian University and a missionary and ethnological museum in the Lateran. His calls for reunion between Rome and Orthodoxy met with little response, but he was more successful in the attention he paid to the Uniate Churches of the east (i.e., the eastern-rite Churches in full communion with Rome). He also at first allowed, and then later approved, the conversations held between Catholics and Anglicans at Malines in 1921-6.

The first scholar-pope since Benedict XIV, Pius XI quietly eased the tensions arising from the Modernist debate. He considered the advancement of science and scholarship as a personal challenge as well as a part of the mission of his pontificate, and among other measures he modernised and enlarged the reading room of the Vatican Library; raised three of its most scholarly Prefects to the Cardinals’ College; founded (Dec. 1925) the Pontifical Institute of Christian Archaeology; built the Pinacoteca for the Vatican collection of pictures; and moved the Vatican Observatory (equipped with new modern instruments) to Castel Gandolfo. He also instructed the Italian bishops to take proper care of their archives and radically reformed (Deus Scientiarum, 24 May 1931) the training and instruction of the clergy. His interest in modern scientific developments was reflected in his installation (1931) of a radio station in the Vatican City and he was the first Pontiff to use the radio for pastoral purposes.

Well informed about scientific research and eager to promote dialogue between faith and science at a moment when Positivism was advancing rapidly, Pius XI also refounded the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1936 with the idea that it would be the ‘Scientific Senate’ of the Church. Hostile to any form of ethnic or religious discrimination in deciding the composition of the Academy, he appointed over eighty Academicians from a variety of countries, backgrounds and areas of research, including such leading scientific figures of the day as: U. Amaldi, N. Bohr, A. Carrel, P.J.W. Debye, A. Gemelli, B.A. Houssay, G. Lemaître, G. Marconi, R.A. Millikan, T.H. Morgan, U. Nobile, M. Planck, E. Rutherford, E. Shrödinger, F. Severi, C.S. Sherrington, G. Vallauri, and P. Zeeman. Emphasising the need to develop the links between science and Christian humanism, he also made Cardinal G. Bisleti, Cardinal F. Marchetti Selvaggiani and Cardinal E. Pacelli (the future Pius XII), Honorary Members of the Academy. The goals and the hopes of the Academy, within the context of the dialogue between science and faith, were expressed by Pius XI in the Motu Proprio which led to its refoundation:

Amongst the many consolations with which divine Goodness has wished to make happy the years of our Pontificate, I am happy to place that of our having being able to see not a few of those who dedicate themselves to the studies of the sciences mature their attitude and their intellectual approach towards religion. Science, when it is real cognition, is never in contrast with the truth of the Christian faith. Indeed, as is well known to those who study the history of science, it must be recognised on the one hand that the Roman Pontiffs and the Catholic Church have always fostered the research of the learned in the experimental field as well, and on the other hand that such research has opened up the way to the defence of the deposit of supernatural truths entrusted to the Church… We promise again, and it is our strongly‑held intention, that the ‘Pontifical Academicians, through their work and our Institution, will work ever more and ever more effectively for the progress of the sciences. Of them we do not ask anything else, since in this praiseworthy intent and this noble work is that service in favour of the truth that we expect of them’.

He was convinced that the truth was the highest form of charity, and he believed that the search for the truth was the principal task of the Academy. The importance he attributed to the refoundation was also reflected in his decision to locate the Academy in the sixteenth-century Renaissance villa, ‘Casina Pio IV’, situated in the Vatican gardens.