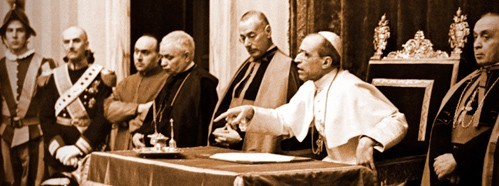

His Holiness Pius XII (2 Mar. 1939-9 Oct. 1958) was the son of a lawyer and descended from a Roman aristocratic family of jurists. Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli was born in Rome on 2 March 1876, attended a state secondary school, and studied at the Gregorian University, the Capranica College, and the S. Apollinare Institute, Rome. Ordained priest in April 1899, he entered the papal service in 1901, and from 1904 to 1916 was Cardinal Gasparri’s right-hand assistant in codifying the canon law; for several years he also taught international law at the Academy of Noble Ecclesiastics. In April 1917 Benedict XV appointed him Nuncio in Munich and titular Archbishop of Sardes, and in June 1920 named him Nuncio to the new German Republic. These were busy years for during the First World War he had to negotiate with the imperial government about Benedict XV’s peace plan (1917), while after the war he agreed concordats with Bavaria (1924) and Prussia (1929). Appointed Cardinal on 16 December 1929, he succeeded Gasparri as Secretary of State on 7 February 1930, and as such was responsible for the concordats with Austria (June 1933) and Germany (July 1933). Although Berlin took the initiative in the latter, Hitler’s repeated violations of it and the deteriorating position of the Church in Germany led to increasing difficulties for the Holy See. In the meantime, Pacelli, an accomplished linguist who had earlier travelled to Britain, paid official visits to Argentina (1934), France (1935 and 1937), and Hungary (1938), and an extensive private one to the USA (1936). While Secretary of State, he was appointed a Honorary Member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1936.

With the Second World War threatening, he was elected at a one-day conclave at the third ballot on 2 March 1939. No Secretary of State had been chosen since Clement IX, but he was the best-known of the Cardinals, and possessed the gifts and experience that seemed suitable to the moment. Pius XII saw himself as the pope of peace and until 1 September 1939 he strove to avert war by diplomatic means, on 3 May calling for an international conference to settle differences peacefully and on 24 August making a radio appeal to the world to abstain from resort to war. Until Mussolini’s entry into the war on 10 June 1940, he worked to keep Italy out of the conflict. He achieved none of these aims but through his efforts and presence Rome was treated as an open city. In his allocution of Christmas 1939 he had laid down the five principles essential for a just and lasting peace. They included practical and spiritual disarmament, the recognition of minority rights, the right to life, the right of every nation to independence, and the creation of more effective international institutions to defend and promote peace. Although convinced that Communism was even more dangerous than Nazism, he did not endorse Hitler’s attack on Russia. Throughout the war he supervised, through the Pontifical Aid Commission, a vast programme for the relief of war victims, especially prisoners of war; and when Hitler occupied Rome on 10 September 1943 Pius XII made the Vatican City an asylum for countless refugees, including numerous Jews.

Unaffected in his teaching office by the war, Pius XII published two major Encyclicals while it was still under way. In Mystici Corporis Christi (29 June 1943) he expounded the nature of the Church in terms of Christ’s mystical body, while in Divino Afflante Spiritu (30 Sept. 1943) he permitted the use of modern historical methods by exegetes of Scripture. Closely linked with the former was Mediator Dei (20 Nov. 1947), which called for the intelligent participation of the laity in the mass. In 1951 and later he reformed the entire Holy Week liturgy, while in Christus Dominus (6 Jan. 1953) and Sacram Communionem (19 Mar. 1957) he standardised relaxations of the Eucharistic fast and the holding of evening masses which wartime conditions had made necessary. Always Marian in his piety, he defined the dogma of the bodily Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven in Munificentissimus Deus (1 Nov. 1950) and devoted Ad Caeli Reginam (11 Oct. 1954) to her royal dignity, leaving open, however, the question of her mediation and co-redemptive role. He was the first to appreciate the Marian importance of Fatima. A conservative note was sounded in Humani Generis (12 Aug. 1950), which warned against the accommodation of Catholic theology to current intellectual trends.

Politically, Pius XII condemned Communism, threatening (e.g. 1 July 1949 and 28 July 1950) members of the party and its promoters with excommunication, and concluded accords regarding the position of the Church with Salazar’s Portugal (18 July 1950) and Franco’s Spain (27 Aug. 1955). In the moral field, he condemned, with Germany in view, the notion of collective guilt (24 Dec. 1944; 20 Feb. 1946), and any kind of artificial insemination (29 Sept. 1949). In Miranda Prorsus (8 Sept. 1957) he sought to lay down guidelines for the audio-visual media, instruments which he used in an extensive and innovative manner in order to communicate with the faithful around the world. Pius XII canonised 33 persons, including Pius X. He also created an unprecedentedly large number of Cardinals, 32 in 1946 and 24 in 1953, drawing them from many countries and reducing the Italian element to one-third. Although the Church suffered severe restrictions and losses during his pontificate, it also made striking advances, the number of dioceses rising from 1,696 in 1939 to 2,048 in 1958, with hierarchies being established in China (1946), Burma (1955), and several African countries. He also sought to encourage relations with the Uniate and Orthodox Churches of the east. Tall, slender, somewhat ascetic in appearance but friendly in manner, he made a profound impression on the millions who flocked to Rome for the Holy Year of 1950 and the Marian Year of 1954, and on the thousands who attended his innumerable audiences.

As a Honorary Member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the person who delivered the inaugural address of the first assembly of the Academy on 1 June 1937, Pius XII evinced a strong interest in the workings of the institution throughout his pontificate. At a time when research was achieving extraordinary results in its investigation into the structure of matter, energy, cosmology, nature, and the function of cells, and new theories were rapidly developing to keep pace with scientific results, Pius XII’s main concern was constantly to prove to the Academicians that there was no conflict between science and faith. Following the strong wish of his predecessor to build bridges between faith and reason, and eager to promote the cause of hard science, he acted to ensure that the Pontifical Academy was a ‘Scientific Senate’ of the Holy See by seeking and securing constant information from it about scientific and technological questions of the day.

Pius XII gave eight papal addresses to the Academy in which he dwelt at length upon major contemporary issues and offered strong doctrinal and moral guidelines for their resolution. Pius XII’s ideas on science were very clear. Addressing the Academy in the session of 1955 he said: ‘The duty of a scientist is to understand God’s design, to interpret the Book of Nature, to explain its contents and to draw from it consequences for the common good’. The Pope’s statement that the experimental method cannot be influenced by philosophical assumptions and that the autonomy of science and of scientific interpretation is legitimate must be underlined. These words enlightened the Church in a field which had caused misunderstandings in the past that had not yet vanished. Indeed, in his first meeting with the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Pius XII affirmed the freedom of scientific research: ‘To you noble champions of human arts and disciplines the Church acknowledges complete freedom in method and research’. This statement expressed a new vision of science, which Pius XII was to reaffirm in all the allocutions given during his Pontificate. Today it can be regarded as the synthesis of an important moment in the history of science and philosophy. The secrets of the microcosm and macrocosm revealed by scientists were considered by the Pontiff as evidence of the Creation. To take into consideration only laws of statistics was a common error of our times: ‘such universal order is not and cannot be the result of absolute blind necessity nor even of fate or of chance and scientists must look for a law which is established by the Mind that rules the Universe’. This was to foreshadow those points of view on the principle of causality, which was to be thoroughly developed in the 1960s, and put forward by some scientists as the only explanation for the order of the whole universe and for the origins of life. When Pius XII learnt that the latest results of cosmological research proposed the existence of an initial event to explain the formation of the universe, he said: ‘Creation in time and therefore a Creator and therefore God. Although still implicit and incomplete these are the words we wanted to hear from Science and that the present generation is waiting for’. This address had a great impact on the scientific world of the time and even today it is widely quoted in works of epistemology. It demonstrated a renewed interest on the part of the Church in scientific questions.

As regards scientific discoveries used as destructive weapons, when addressing the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1941, at the time when ‘the war tears the world to pieces and employs all available technological resources to destroy’, Pius XII reminded those present that in the hands of man science can become a double-edged weapon capable both of curing and killing. In this period, the Pontiff attentively followed ‘the incredible adventure of man involved in research into nuclear energy and nuclear transformations’ through personal contacts with scientists and the reading of scientific works. In particular, in response to a suggestion made by Max Planck, he warned the world about the imminent dangers of atomic war and in his address to the Pontifical Academy of 1943 appealed to world leaders to act together to secure its prevention: ‘Although it is still unconceivable to take technical advantage of such an unforeseen achievement, it does break the ground for multitudes of possibilities which make the setting-up of uranium reactor no longer a utopia. It is, however, essential to prevent the process from taking place as an explosion because otherwise the consequence could be catastrophic not only in itself but for the whole Planet’. Unfortunately the United States had already passed the experimental stage and two years later the first nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. In 1948 Pius XII admitted sadly that nuclear energy had been employed for destruction and death: ‘The nuclear bomb, the most terrible weapon that the human mind has ever conceived’. The tragedy of Hiroshima made him realise that a future conflict, to which science would make its contribution, would be fatal to the world: ‘What calamities a future conflict would hold in store for mankind, if it proved impossible to stop or slow down the use of every new and sophisticated scientific invention’. His appeal then followed: ‘We should mistrust the science whose main objective is not love’. He was not just thinking of nuclear weapons, but also of the whole arsenal of sophisticated systems, from missiles to chemical, biological and conventional weapons which were the result of the use and development of scientific research. He was adamant in his views and declared: ‘Each branch of science governed by scientists worthy of the name and you in particular tends towards the realisation of love for your fellow-men’. Taken in itself each branch of science leads to love, he said when Marconi was still alive, and added: ‘As regards practical applications, it practices love for men at whose service it places itself to provide them with every kind of good things’. His concerns about nuclear energy as a war weapon increased after its use against Japan. For this reason, he repeated the view that it is possible to make an immoral and barbaric use of the most beautiful achievements of science. He was also keen to stress that reason led to faith and that science led to a perception of transcendence. In his address of 21 February 1943, for example, he declared: ‘you seek the law, which is precisely an arrangement of reason of One Who governs the universe and has fixed in it nature and the movements of its unconscious instinct’.

Foreshadowing a later initiative taken by John Paul II with his public return to the Galileo case, Pius XII was to write in the marble plaque he placed specially in the Academy, to commemorate the role played by Pius XI in the refoundation of the Academy, that Galileo had been a leader of the scientists who had established the Accademia dei Lincei, the precursor of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

Pius XII appointed forty-one new members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences including such distinguished scientists of the time as: E.V. Appleton, L. de Broglie, E.A. Doisy, A. Fleming, O. Hahn, W.C. Heisenberg, W.R. Hess, C.J.F. Heymans, M.T.F. von Laue, L. Ruzicka, F. Severi, A.W.K. Tiselius, Albert Ursprung and A.I. Virtanen; and also made Cardinal Maglione and Cardinal Pizzardo Honorary Members. Reflecting his interest in research, he also promoted important excavations (1939-49) under St. Peter’s aimed at identifying the Apostle’s tomb.