In his last address to the Pontifical Academy, Pius XI dwells at length upon the nature and purpose of science. He observes that the subject of science is the ‘reality of the created universe’ and that scientists through their research draw near to ‘incomparable heights’. He describes the joy he had experienced in contemplating nature from mountain peaks (he himself was a mountain-climber) and remarks that scientists in their work share similar ‘spiritual delight’.

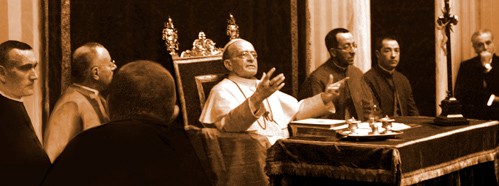

The Holy Father began his speech by saying that he intended to address not only a word of blessing to the participants but also, as was to be expected of a father, to express an affectionate greeting to the eminent and elect sons he had about him – the honourable members of the Sacred College and the delegation of Cardinals, and also those others recommended to him for various reasons, but for the most part on account of scientific knowledge which owed so much to their work. They themselves – he did not hesitate to say – owed much to their subject because of the pure, worthy, truly elevated joys which only science, the study of truth, can give. It was this point which led His Holiness to address a special speech to the cultivators of science, to scientists of such great merit and distinction.

The Holy Father continued saying that we are in an era in which it is difficult to avoid the influence of the age: Dies mali sunt1 – they are not favourable towards serene things. However, all should be grateful to the Church, the great Mother and Teacher who suggested and presented a special subject for that meeting, itself called to illuminate and make sweeter our spiritual horizon. She had even almost prepared it by a happy combination of time and place (and we know Who it is that ordains these coincidences!). All ought to be grateful to the Church that the meet

...

Read all

In his last address to the Pontifical Academy, Pius XI dwells at length upon the nature and purpose of science. He observes that the subject of science is the ‘reality of the created universe’ and that scientists through their research draw near to ‘incomparable heights’. He describes the joy he had experienced in contemplating nature from mountain peaks (he himself was a mountain-climber) and remarks that scientists in their work share similar ‘spiritual delight’.

The Holy Father began his speech by saying that he intended to address not only a word of blessing to the participants but also, as was to be expected of a father, to express an affectionate greeting to the eminent and elect sons he had about him – the honourable members of the Sacred College and the delegation of Cardinals, and also those others recommended to him for various reasons, but for the most part on account of scientific knowledge which owed so much to their work. They themselves – he did not hesitate to say – owed much to their subject because of the pure, worthy, truly elevated joys which only science, the study of truth, can give. It was this point which led His Holiness to address a special speech to the cultivators of science, to scientists of such great merit and distinction.

The Holy Father continued saying that we are in an era in which it is difficult to avoid the influence of the age: Dies mali sunt1 – they are not favourable towards serene things. However, all should be grateful to the Church, the great Mother and Teacher who suggested and presented a special subject for that meeting, itself called to illuminate and make sweeter our spiritual horizon. She had even almost prepared it by a happy combination of time and place (and we know Who it is that ordains these coincidences!). All ought to be grateful to the Church that the meeting was taking place towards the end of Advent, that is, towards the Vigil of Christmas – the great and beloved solemnity, itself a source of sweetness, joy and teaching for all, including scientists. The Sacred Birth which is about to be celebrated is the scientist’s great feast, it is the particular solemnity of the cultivators of science. There were good reasons for it being so, and, having around him such illustrious scholars, the Holy Father wished to recommend it as such.

What exactly is science? What is the subject of this science to which they dedicate themselves with such success? The complex subject of science, of all the sciences, is the reality of the created universe. Whether we are considering the depths of space, the reaches of the sea or the gigantic mountains, or whether we work with invisible dust, the most minuscule and impalpable organism, we are always in the sphere of the created, the ambit of the universe. The birth of Jesus Christ is, as the Church remembers it with her affection and in her continuous worship, the Birth of the Divine Word made flesh and appeared amongst us: Verbum caro factum est et habitavit in nobis.2 See how these beloved sons come to meet the Creator of the object of their sciences. He it is Who has prepared for each and every one of them the object of their studies in all the minute and varied characteristics of the various branches of the diverse disciplines. In a special way at this time the Church opportunely recalls every day in the Sacred Liturgy all over the world, this great and grandiose truth: the great truth which returns in all its immense richness on the occasion of the Christmas Mystery. Christmas is the birth of the Incarnate Word, the Divine Word, of Whom the Evangelist spoke so effectively. The human eye has truly never seen so far, closed if you like to the natural light, but open to the supernatural and divine light. The Apostle John wrote the stupendous words In principio erat Verbum, et Verbum erat apud Deum, et Deus erat Verbum. In ipso vita erat.3 The human mind has certainly never been raised so high in its thought. Never have human words expressed such exalted concepts. With such an expression it seems, so to speak, as if the widest possible edge is lifted off on the Mystery of the Divinity, the mystery of the Intimate Being itself of the Divinity.

In principio erat Verbum: words which at once express the thought – and what would words be without thought? We distinguish the mental word, the spoken word, the verbal word – in principio erat Verbum. The word was in the heart of the divinity, He was Himself the Divinity, He enjoyed all the Divinity. The thinking Divinity, the thought Divinity, as our poor and feeble way of speaking would say. The Word which tells God its essence, its being. In ipso vita erat: behold the procession of life, of thought, of affection; behold the Holy Spirit, that Spirit in which, through which, God – as our great poet said loves Himself and smiles: O luce eterna che sola in te sidi – sola t’intendi, e da te intelletta – e intendente, te ami e arridi!4

God concedes to all of us to see something of such sublime splendours: O luce eterna che sola in te sidi! Does the Mystery perhaps vanish before this inundation of light? No, the Mystery remains! But when mistaken notions are refuted what beauty and what things take their place. The idea, for example, of those who argue that God needed to create the world to remove Himself from the tremendous solitude of His eternity. It is rather a matter of a most beautiful eternity: The Father, The Son and The Holy Spirit: a divine infinity of life in a threefold infinity of reality, of personality.

If that might seem a digression it was on the contrary fully within the theme originally proposed, and the Holy Father was pleased to explain it with gracious stress. Et Deus erat Verbum, he continued, omnia per ipsum facta sunt.5 All this universe was made by Him, through Him: therefore everything was made through this Word, the expression of a mental word of a thought which was never considered so luminous, profound, extensive. It is a divine thought: it is God Who thinks Himself: O luce eterna che sola in te sidi – sola t’intendi, e da te intelletta – e intendente, te ami e arridi!

Everything was made through the Word, through the great Artificer of the universe. No force or beauty can be added to this expression, but it is not surprising that elsewhere the same Divine Word explaining the immense beauty of creation says of God: Omnia fecit in pondere, numero et mensura.6 It is like going into an immense laboratory of chemistry, of physics, of astronomy! Few indeed can admire the profound beauty of such words as well as those who make sciences their profession.

In pondere: you who weigh the stars – His Holiness explained – and calculate the specific weight of bodies and even of atoms; in numero, you who number tiny microscopic things, and count the years of light; in mensura, you who, as you weigh the stars, so you measure the astronomic intervals between them, and the oceanic distances. No one can understand better than you the exactness of these words: that everything is made by God in pondere, numero et mensura.

Because of the origin of the world in this Divine Word, through whom everything was made (per quem omnia facta sunt), is not reflection on such a sublime truth worthy not just of the most diligent attention, but also real devotion from the men of science? Here there is not involved just the common piety of each individual Christian: No! To be a scientist, to be one who sees beyond the material surface of things, is enough to elevate oneself to incomparable heights, and to approach such magnificence.

Omnia per ipsum facta sunt … in ipso vita erat. It was something the August Pontiff did not believe superfluous for his beloved sons to hear: even if they were not his own words he had recalled them hoping that in this way he might respond to the pleasing thoughts they had expressed. Something which would be accepted and adapted to their intelligences, and find its proper place in their daily studies in which the universe reveals itself and points to this Word per quem omnia facta sunt.

He then returned to the other phrase of Sacred Scripture that concerned the work of the Word of God through all that is created: everything was made in pondere, numero et mensura. The created world receives weight, number and measure through the hands of God. This is true for everything: for the greatest as much as for the smallest. But furthermore, Sacred Scripture also takes care to describe to us everything in the world which is of consolation and delight. In the book of Wisdom, the Word of God is spoken of again. It takes its very name from the divine Wisdom and is described to us as the Verbum mentis, the ‘thought word’. It is identified in the omnipotent work of creation, about which wisdom itself is pleased to raise up incomparable praises.

It is a delightful passage.

Ab aeterno ordinata sum: from all eternity I have been constituted. This is the first point of contact with the expression of John: In principio erat Verbum. Thus also, Nondum erant abyssi et ego iam concepta eram: I had already been generated even before the abysses existed. The Divinity thought itself and the Divine Wisdom was conceived and generated. Necdum fontes aquarum eruperant: and the springs of water had not yet gushed forth; necdum montes gravi mole constiterant: nor had the mountains risen in their great mass; adhuc terram non fecerat et flumina, et cardines orbis terrae: He had not yet made the earth, nor the rivers, nor the foundations of the world: before all things and before everything I existed.

After this introduction, the Holy Book continues with a style which is both wonderful narration and admirable poetry. When the hand of God was forming the whole creation, I, His Wisdom, was there. Quando praeparabat caelos aderam; quando certa lege, et gyro vallabat abyssos: when He prepared the heavens, when He fixed the depths in the regular pattern of their limits, I was present. Quando aethera firmabat sursum, et librabat fontes aquarum: when He set the atmospheres above and arranged the springs of water; quando circumdabat mari terminum suum, et legem ponebat aquis, ne transirent fines suos; quando appendebat fundamenta terrae:7 when He surrounded the sea with its boundary, and set a law for the waters so that they would not pass beyond their limits; when He fixed the foundations of the earth; – cum eo eram cuncta compones: with Him I was arranging all things.

The Poet was surely thinking of this when, comparing the earth to a ship safe on its anchors, he exclaimed: dei cieli – nei lucidi porti – la terra si celi attenda sull’ancora – il cenno divino – per novo cammino.8

See how much the Holy Bible tells us with regard to this divine uncreated Wisdom of the Word per quem omnia facta sunt! How could we approach such an inspired passage without a profound sense of admiration? And not that here only the visible universe is mentioned. There is besides the supernatural universe which is not seen, but which exists with all its sublime realities. Nevertheless at the simple consideration of the basic fact of the visible universe one is spontaneously brought to celebrate the latter, the time beyond life and death, and the glories of its Author and Creator, to arrive at that radiant end justly referred to by the same poet as: Veggenti e non veggenti – unica notte involve; e d’altri fermenti – esce l’alba, che solve – del creato il mistero – e ci posa nel vero.

A most consoling reality, the Holy Father explained, which causes a hymn to the Divine Wisdom to spring up in our soul. A hymn to the Divine Word for these intimate relations of the Divine Being with the divine work. In principio erat Verbum … et Deus erat Verbum … omnia per ipsum facta sunt: … in ipso vita erat. What light is shed by such thoughts. What splendours which make the soul rise up from the created world to higher, vaster, more incommensurable realities!

The Holy Father himself, the old priest and old mountain climber, remembering some episodes from his youth, was pleased to recall that right on the highest peak he had reached, he had fully understood the meaning of some texts of Sacred Scripture. On one occasion at 4630 m. amid other summits of similar size, the inspired image of the prophet Habakkuk appeared to him in all its brilliance. These enormous heights like giants seemed to lift their arms up to heaven thus seeming still bigger and still higher: Dedit abyssus vocem suam: altitudo manus suas levavit.9 The Holy Father had never before seen the words of the prophet realised in such a vivid way: mountains among the greatest mountains seeming to soar up as if alive, with a self-renewing force, towards new more daring heights, towards the depths of the heavens.

The August Pontiff was pleased to mention these elevated considerations. He knew how the beloved sons about him would have shared with him the great spiritual delight that followed. He wished that the Lord would make the interior life and the life of study of each one enjoy some abundant rays of that luce intellettual piena d’amore; – amor di vero ben, pien di letizia; – letizia che trascende ogni dolzore.10 It is true, the Holy Father continued, that love and supernatural light were spoken of here, but it is also true that one arrived at it by lingering a little at the marvellous concept of the visible universe. The Holy Church herself, teacher of faith and truth, invites us to this. It is precisely with that faith, with that truth, that we can come closer to the infinite light of God: O luce eterna, che sola in te sidi – sola t’intendi, e da te intelletta – ed intendente, te ami e arridi!

With these thoughts the Holy Father renewed his wishes that the participants could have a Holy Christmas, and that they might enjoy it as they merited. In the ineffable presence of the great Mystery of the Incarnation of the Word of God he wished to repeat all his other paternal desires for each and everyone. He hoped that from it an intense and beneficent light might break forth and spread into all the areas they wanted, with many good gifts for everyone and everything they had in their minds and hearts at that moment.

1 St. Augustine, Sermo 84.

3 Ibid. 1:1.

4 Paradiso, Canto XXXIII, 124-126.

5 Jn 1:3.

6 Ws 11:20. Cf. St. Augustine, Sermo 8 Conf., Bk. XIII.

7 Pr 8:24-29.

8 Giacomo Zanella, Sopra una conchiglia fossile

9 Hab 3:11.

10 Paradiso, Canto XXX, 39-42.

Read Less