Sive vivimus sive morimur Domini sumus.

(Rom. 14, 8)

The prolongation of life, which has been a constant preoccupation of humankind, has long been a reality. Average lifespan has increased and will continue to do so. This is due to advances in medical knowledge, immunization, sanitation, epidemiology, biostatistics, etc. New technologies make it possible to keep sick patients alive, who formerly would have soon died. Two examples of these technologies are the respirator, which saved a large number of poliomyelitis patients when that deadly infection was very frequent, and renal dialysis, which is keeping many patients alive and has saved many people affected by acute renal disorders.

The techniques for the artificial prolongation of life are steadily improving, but current development creates great and ever-increasing moral, scientific, social and economic issues. From the economic point of view, the artificial prolongation of life weighs heavily on the budget of governments, as it does on families in countries without social security. Although the value of life cannot in any way be measured in monetary terms, we cannot deny that the economic problem exists.

The main question that arises is to know when physicians should or can discontinue the means which are keeping their patients alive. Physicians have the duty to analyze all the factors that must weigh on their decision to stop artificial means of life support. This is a difficult decision that involves the gift of life, which we must preserve with the greatest possible care. Physicians must be guided by their conscience and medical knowledge when, at the end of a fight for the survival of a patient, they have to decide whether life is irreversibly lost. It is a tragic situation. What physicians can never do is interrupt therapeutic and spiritual care, or material comfort, which have to be provided until the end. It is inadmissible to cause the death of the patient, whether by pharmacological or physical means.

...

Read all

Sive vivimus sive morimur Domini sumus.

(Rom. 14, 8)

The prolongation of life, which has been a constant preoccupation of humankind, has long been a reality. Average lifespan has increased and will continue to do so. This is due to advances in medical knowledge, immunization, sanitation, epidemiology, biostatistics, etc. New technologies make it possible to keep sick patients alive, who formerly would have soon died. Two examples of these technologies are the respirator, which saved a large number of poliomyelitis patients when that deadly infection was very frequent, and renal dialysis, which is keeping many patients alive and has saved many people affected by acute renal disorders.

The techniques for the artificial prolongation of life are steadily improving, but current development creates great and ever-increasing moral, scientific, social and economic issues. From the economic point of view, the artificial prolongation of life weighs heavily on the budget of governments, as it does on families in countries without social security. Although the value of life cannot in any way be measured in monetary terms, we cannot deny that the economic problem exists.

The main question that arises is to know when physicians should or can discontinue the means which are keeping their patients alive. Physicians have the duty to analyze all the factors that must weigh on their decision to stop artificial means of life support. This is a difficult decision that involves the gift of life, which we must preserve with the greatest possible care. Physicians must be guided by their conscience and medical knowledge when, at the end of a fight for the survival of a patient, they have to decide whether life is irreversibly lost. It is a tragic situation. What physicians can never do is interrupt therapeutic and spiritual care, or material comfort, which have to be provided until the end. It is inadmissible to cause the death of the patient, whether by pharmacological or physical means. A patient's care must be the constant preoccupation of physicians, and may lead them to the legitimate use of narcosis.

Pope Pius XII, on May 24, 1957 (*), in his address to a group of physicians and surgeons, gave us the guidelines as to what should be done. He said that God only “obliges us to use ordinary means (according to the circumstances of the persons, the places, the times and the culture), that is, those means which do not impose any extraordinary obligation on oneself or on anyone else”. Furthermore, he also answered positively to the question: “Can a physician remove the respiratory apparatus before the definite cessation of the circulation?”.

As a matter of fact, the physician's treatment of the extremely sick involves serious issues around facts, morals and rights: facts concerning the patient's condition and the need or usefulness of any intervention; morals and rights as to the need for the intervention.

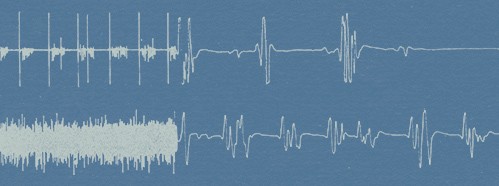

Another problem which has always existed, and has become more important because of organ transplants, is the determination of the exact moment of death, since organs must be transplanted as soon as possible after the death of the donor. A large number of medical associations have debated this issue. The general consensus was that since, from the biological point of view, human activity corresponds to cerebral activity, it is the cessation of this activity that determines the state of death. In general, a flat electroencephalogram taken at different intervals is considered as the sign that human life has ended. However, the number of EEGs to be carried out, and the interval between them, are still under debate.

The Working Group thus studied the problems of the prolongation of life and the determination of the condition of death under various aspects.

(*) Discorsi e Radiomessaggi di Sua Santità Pio XII, Vol. XIX, p. 617.

Read Less